知识中心

动态称重 – 简介

本页内容更新于2025年12月12日Designing a vessel weighing system requires careful consideration of mechanical structure, load cell selection, environmental Dynamic weighing applications measure an object while it is in motion. From products on a conveyor belt, to parcels in a sorting station, to pallets on a distribution line, dynamic scales must be engineered for durability, long-term reliability, and a focus on high-speed accuracy. This application note covers the fundamental design principles, load cell technologies, mechanical and installation considerations, calibration, and system integration guidelines.

Content:

- System Challenges and Core Components

- Importance of Dynamic Weighing

- Core Components

- Accuracy

- Load Cell Selection and Sensor Performance

- Natural Frequency

- ANYLOAD Model Examples

- Environmental Considerations

- Signal Processing

- Dynamic Calibration and Verification

- Load Cell Installation Recommendations

- Legal and Regulatory Considerations

- Conclusion

- Appendix A — Example Load Cell Specification

System Challenges and Core Components

Dynamic Weighing Challenges

- High-Speed Response

The load cell sensor needs to reach a stable state and output a reliable signal within milliseconds and reset just as fast to process the next item to be weighed. There is a careful balance that must be struck between sensitivity (for high accuracy) and stiffness. Increased stiffness will increase response speed but limit deflection, resulting in lower sensitivity. - Long-Term Stability

As these are often found in production lines, the sensor must remain accurate for long service spans as downtime can be unpredictable and extremely costly. The working conditions can be tough and the conveyor may run nonstop for extended periods of time, requiring reliable precision without stopping production for service frequently. - Vibration Reading Mitigation

The constant moving of the production line motors and items are the main source of weighing interference here. The sensor needs to be able to overcome the vibration induced in the line to achieve accurate weighing. This can further be improved through filtering or other software techniques with the raw load sensor signal.

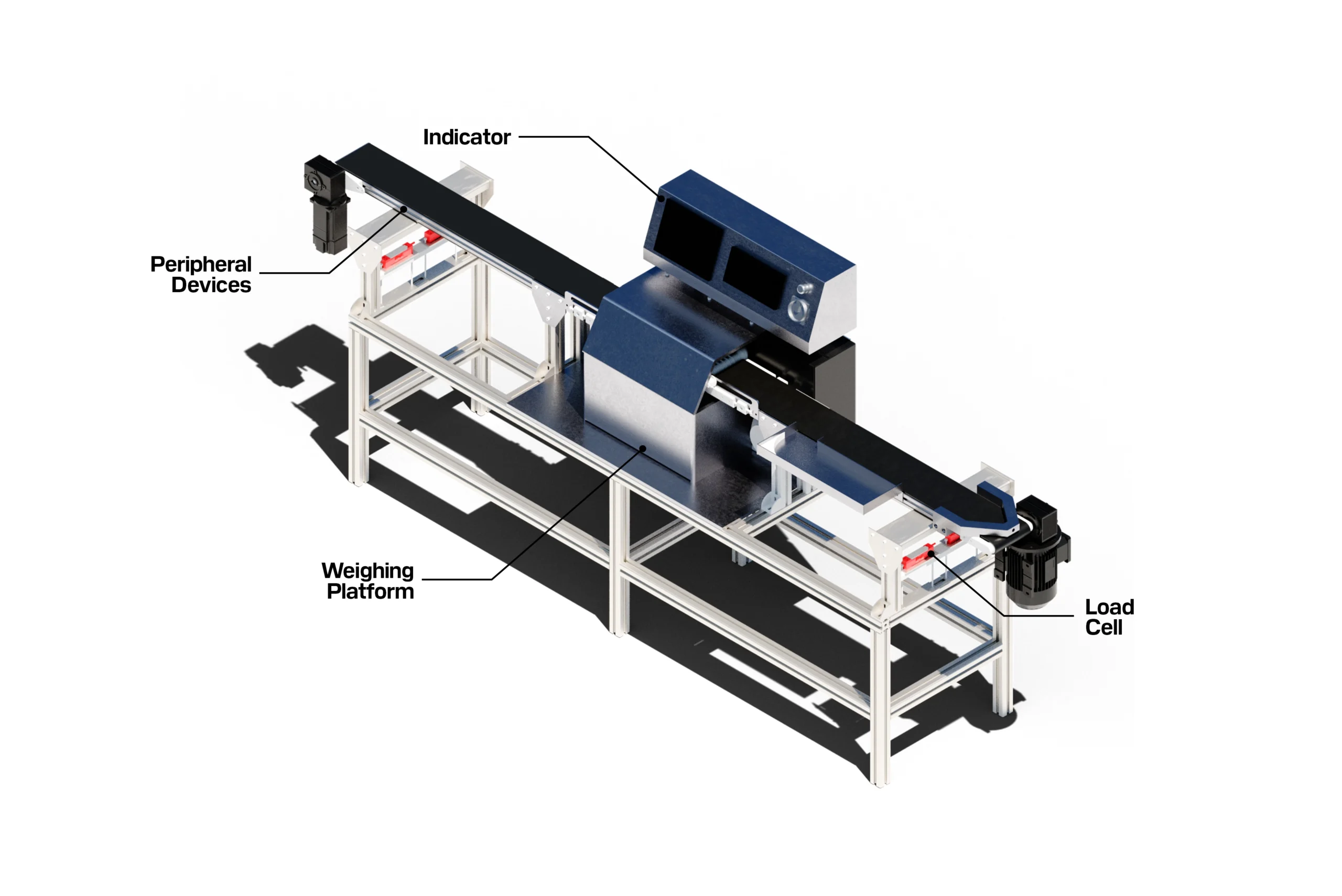

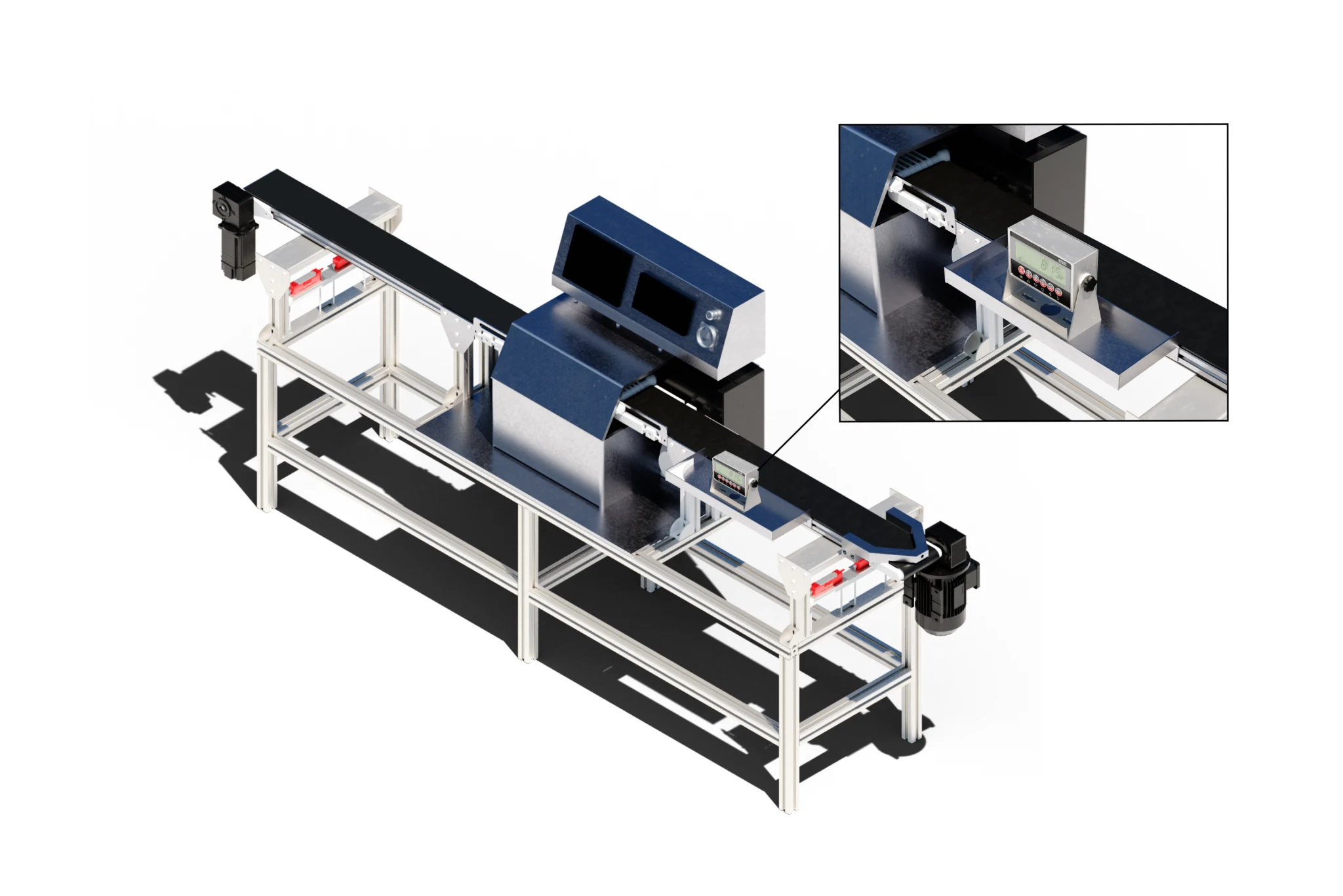

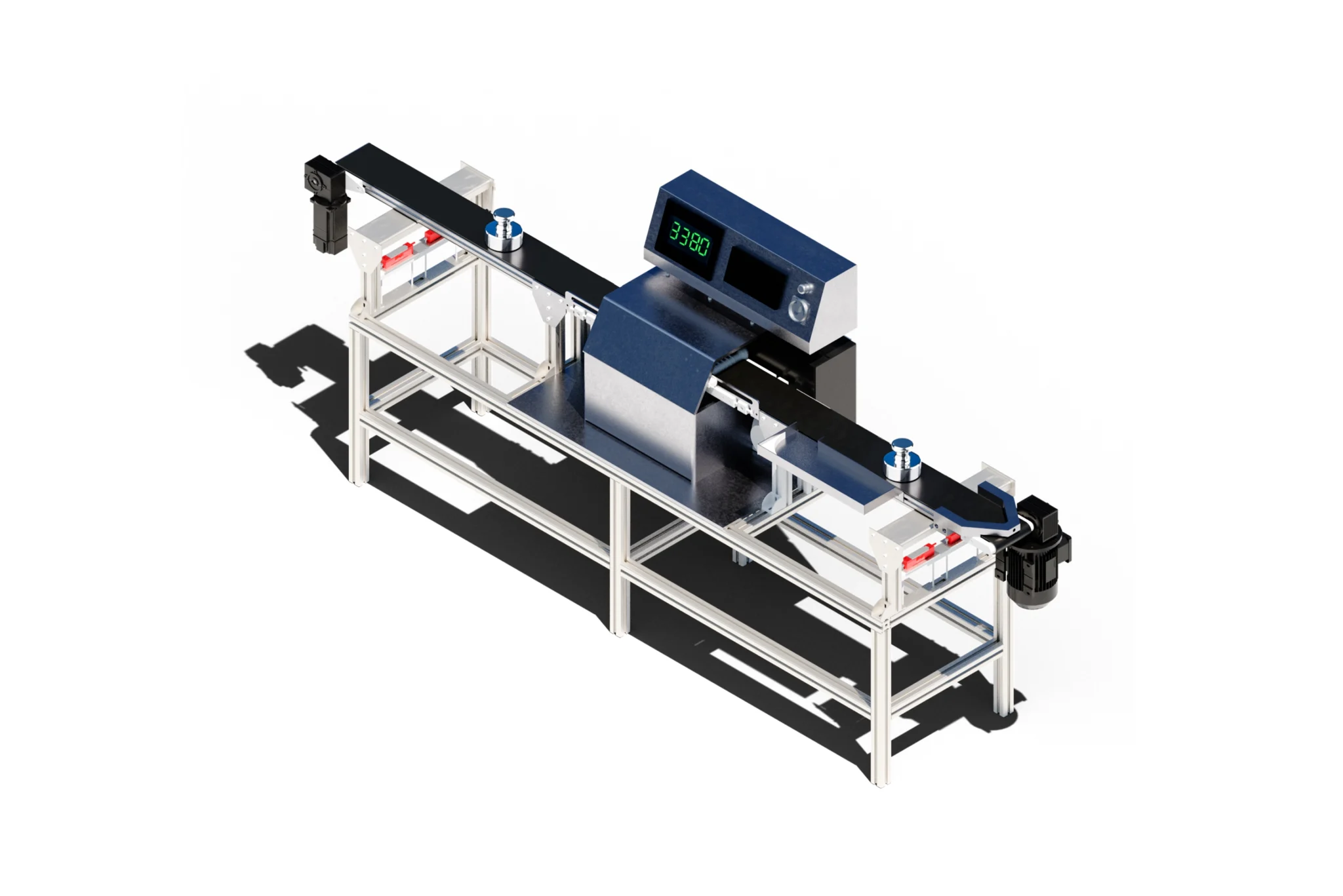

Figure 1: Conveyor System Example

Importance of Dynamic Weighing

Dynamic weighing is most valuable when integrated directly into an automated manufacturing or control system environment as it can quickly and accurately weigh items without the need to wait for a static weighing stage. Dynamic systems can quickly quantify weight, speed, and relay that information to mechanical sorters for quality, batching, rejection, or simply populating a database for traceability used in record keeping and compliance.

Figure 2: Batch Mixing Control Amount in Each Package

Dynamic systems can also be used in conjunction with vision or dimension checks for more robust quality checks and a larger variety of controllable parameters along the production line.

Core Components

A dynamic weighing system is typically comprised of mechanically optimized weighing platforms, one or more high-speed load cells, a real-time indicator or PLC interface, and peripheral devices related to the assembly line.

- Weighing Platform

The weighing platform (sometimes completely hidden underneath a moving component such as a compliant conveyor belt) must be rigid. - High Speed Load Cell

Designed to have a higher than average natural frequency to increase the response speed for stability in high speed applications. - Indicator/PLC

The indicator will require a high sampling rate to ensure an accurate and stable reading can be drawn from the load cell(s) used. - Peripheral Devices

This encompasses any other components required to ensure operation of the scale, such as the conveyor belt, pneumatic sorters, diverters, data logging components, and others.

Figure 3: Core Component Diagram

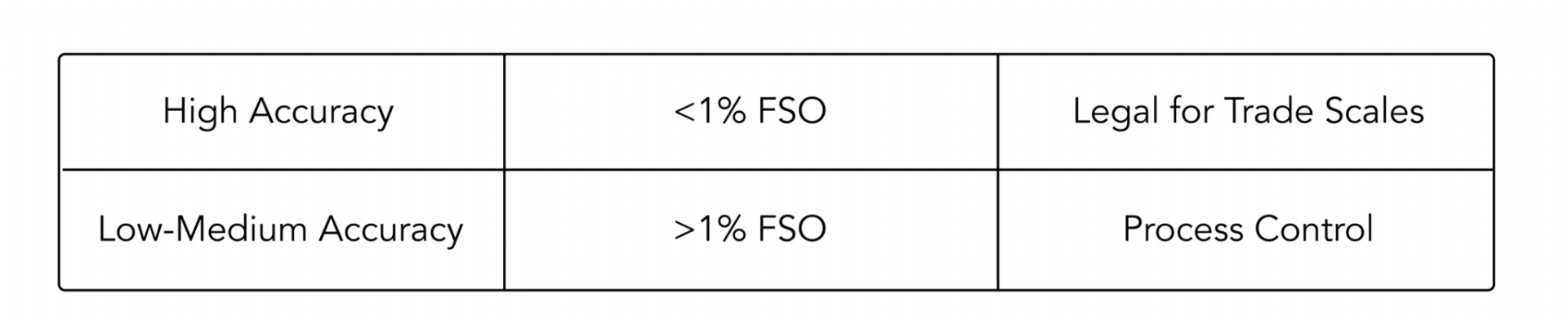

Accuracy

Accuracy Requirement Breakdown Table

Accuracy in a dynamic weighing application is a combination of sensor performance, mechanical structure design, signal processing, and operating environment conditions. Unlike static scales where the object is at rest, the weighing window in a dynamic application is very short, oftentimes less than a fraction of a second. Accuracy classes, while not entirely quantified, typically fall into two categories: legal for trade, and process control.

Load Cell Selection and Sensor Performance

Load cells are the most important component to consider when designing a dynamic weighing system. Unlike conventional static weighing, load cells for dynamic applications must be designed to measure and settle very quickly. The load cells must also manage rapid and repeated loading, requiring good anti-vibration characteristics to handle repeated impact and high fatigue life for enduring millions of cycles.

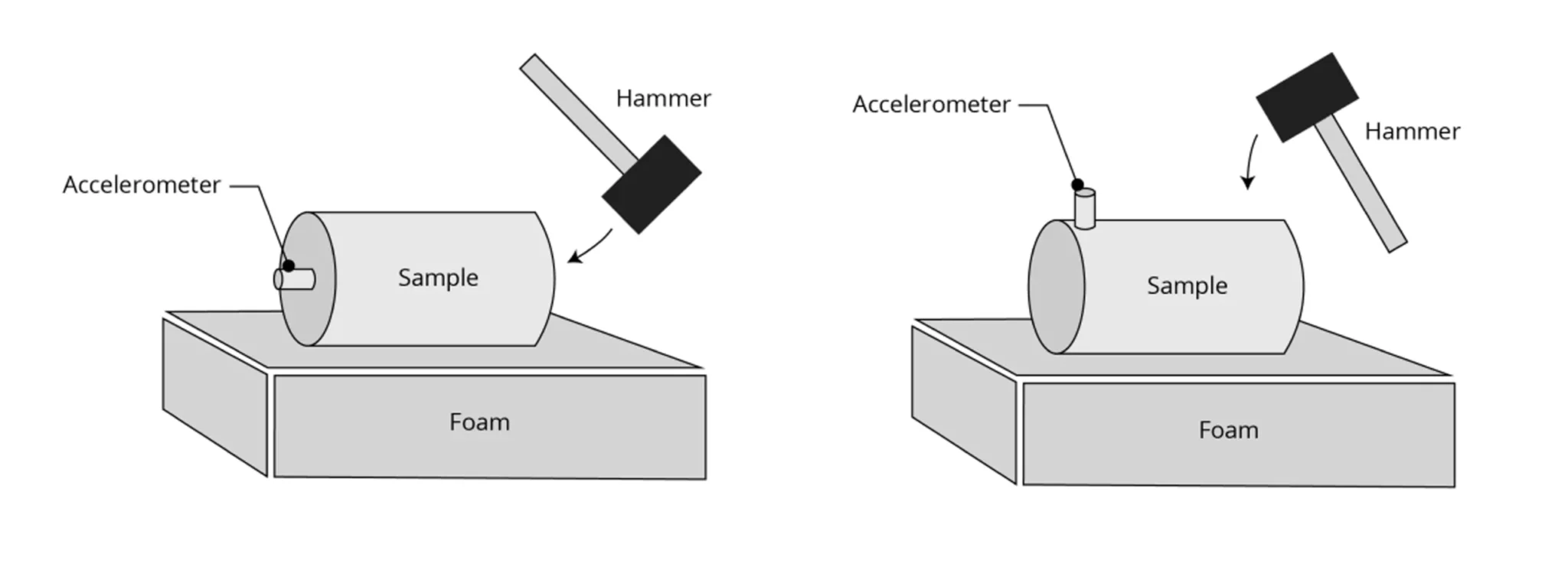

Natural Frequency

This frequency is the rate at which a load cell or mechanical system will oscillate when displaced and released without a continuous external force applied. Hz is expressed as the inverse of a second, or s-1. In dynamic weighing this means two things:

- Determines how fast the load cell can respond to a load and settle to a stable measurement.

- A high value means it’s unlikely to share it with the surrounding machinery, increasing resistance to vibrations induced by systems around it.

If the natural frequencies of two objects match, unaffected structures may begin to vibrate on their own, inducing noise into the measurement. Load cells intended for use in static applications can have natural frequencies closer to 100-200Hz or lower depending on the size of the load cell as they typically have 1-3s to settle when weighing an object.

Figure 4: Natural Frequency Test Setup

There are several common environmentally born natural frequencies. Some examples include:

- 2-50Hz for conveyor belts with rollers (smaller rollers have higher natural frequencies)

- 50-60Hz for power electronics

- 100-300Hz for motor vibrations

- 30-400Hz for machine frame resonance, depending on how heavy duty the frame and panelling is.

These vibrations are typically transmitted by direct mechanical contact with the load cell support structure. For dynamic weighing, the load cell natural frequency must be higher (≥500Hz) to avoid resonance with other components in the system and allow a faster settling time for rapid weighing.

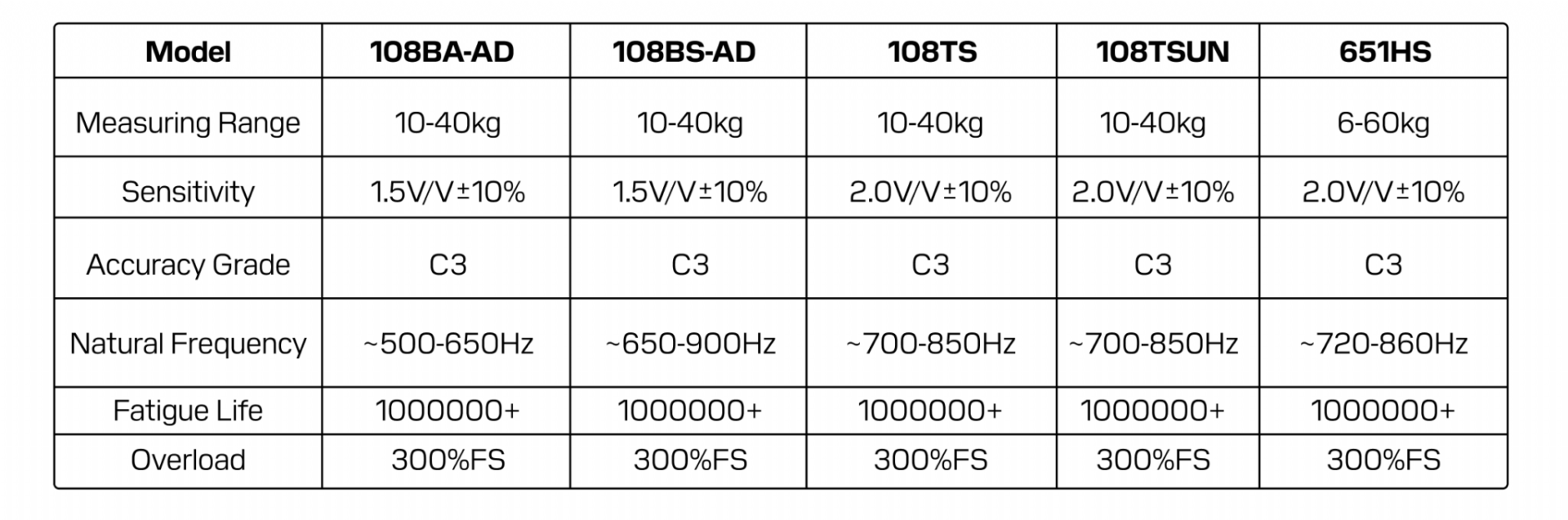

ANYLOAD Model Examples

Environmental Considerations

To get accurate results in a large and complex system, environmental factors must also be factored into the system design process. Some site considerations include:

- Isolation vs. Integration

Some systems may incorporate a suspended subframe or something similar, to completely decouple the loading platform from up or downstream belt vibrations. Others may integrate them directly into the system to minimize footprint. System requirements will inevitably dictate which is more feasible. Generally, isolation is preferred when there are significant sources of noise or higher precision is required. - Environmental Protection

For processes with sanitary requirements, sealed enclosures may be required with use of stainless steel load cells rated for washdown use, particularly in food or pharmaceutical uses. - Temperature Compensation

Depending on the region it is installed or the specific operating conditions of the dynamic system, adequately temperature compensated load cells will need to be implemented to maintain accuracy in all conditions.

Signal Processing

The nature of a dynamic weighing environment means the raw load cell data will carry a larger amount of transient noise than in static weighing environments. The optimized structure of the load cell when combined with effective signal conditioning will ensure a true weight value quickly, and repeatably.

Figure 5: Belt Scale Indicator Located on the Floor for Operator Use

Most systems along a production facility will integrate into a larger PLC-based control scheme where more powerful processing can be performed, but for manual checking stages, a basic indicator with precision A/D converters and an array of filtering algorithms can also provide adequate mitigation of high-frequency noise.

More advanced indicators designed for belt scale applications also include speed sensors and parameters for belt length, allowing for adjustment of the stabilization window based on the instantaneous belt speed or a configurable length average. The type of indicator will depend on the needs of the workers, and the level of automation present in the plant.

Dynamic Calibration and Verification

Calibration for dynamic scales differs from static calibration due to the motion effects of the site. Two common approaches exist to perform calibration:

1. Reference Product Runs

- Running a set of calibrated pieces at production speed and pacing

- Repeated measurements may be required to have better data values

- Recording the measured value

- Adjusting scale factors and filtering strength/speed until results are within specified tolerance

Figure 6: Calibration Weight Passing Over Checkweigher

2. Dynamic Substitution

- Typically reserved for high capacity systems.

- Running a large, calibrated mass/set of masses across the scale.

- Repeating the measured value using bulk material, until the value is identical to the dynamically weighed value of the calibrated mass.

- Add the calibrated mass to the bulk mass and repeat the process until the desired capacity is met with enough passes to get consistent results.

Regular system tuning should be performed by doing periodic verification runs (i.e. once per shift) using traceable weights or equivalent, documenting initial and last measurements during the specified in-line verification period. Environmental information can also be recorded for systems that are more sensitive or experience more drastic changes in environmental conditions.

Load Cell Installation Recommendations

Fixtures for dynamic application weigh modules can be different from their static counterpart due to the more involved system integration; here are some practical tips for general installation:

- Location

– Use rigid, well-supported structures

– Isolate it from machine frames that create vibrations or shock loads - Structural Considerations

– Keep away from large cantilever or overhang spans to minimize deflection in the weigh platform - Adjacent Equipment

– Ensure electrical shielding and grounding is proper

– Keep cables away from components that may generate noise

– If washdown safety is required, position junction boxes and other components in accessible, but protected locations with IP-rated connectors and seals

Legal and Regulatory Considerations

When used in commerce and sold directly by the weight specified, the system must follow legal-for-trade regulations. These scales can still be used for process and quality control without certification but an approved static weighing stage must be added to the end of the process line to complete legal, traceable weight measurements before sale.

Unlike static scales where individual components are certified, obtaining legal-for-trade status on a dynamic weighing system (i.e. belt scale) requires the entire system to be tested for each site install to verify accuracy, repeatability, zero stability, software security, and sealing provisions across multiple flow rates and belt speeds. First, the zero stability is tested by running multiple belt loops and observing any drift, later followed by material tests using pre-weighed items or a verified scale at the end to gather the passed material for comparison against the measured dynamic scale value. Detailed testing standards are outlined in NIST Handbook 44 for NTEP approvals or OIML R50-1

While metrology authorities such as NTEP, NIST, or OIML are the authoritative bodies that set the performance regulations in place, enforcement and inspections are typically conducted by a localized metrological regulatory agency, often called a department of Weights and Measures. The local agencies are responsible for enforcing annual inspection of legal-for trade installations and facilities.

Conclusion

Dynamic weighing varies drastically from system to system as the level of integration required is far greater than most static applications. Special focus is placed on choosing sensors with high natural frequencies, robust signal processing, and calibration procedures. When properly executed, dynamic weighing systems provide verified high throughput, reducing waste and maximizing quality by enabling automated decision making on production or sorting lines.

Appendix A — Example Load Cell Specification

The following is a condensed list of typical items that should be checked when selecting a sensor for dynamic weighing:

- Measuring Range: Should be chosen based on expected single-piece mass and overload allowance, including shock load (if applicable) and the mass of the weighing platform.

- Sensitivity: Typically ranges from 1.5-2.0mV/V for all dynamic application optimized load cells.

- Natural Frequency: >500Hz is suitable for most applications, with higher speeds requiring higher natural frequencies to ensure a fast and stable reading.

- Fatigue Life: Most dynamic load cells are tested to >1 000 000 cycles to ensure a long service life in all applications.

- Temperature Compensation: Load cels are typically compensated between -10°C to 50°C, ensure the range is suitable for the installation.

- Ingress Protection: Considered for washdown applications, IP67 will be required to ensure operation is not affected by water ingress.

- Overload Protection: Load cells are typically rated for 300%FS before failure, if larger margins are required, a higher capacity load cell should be chosen.